| Matt King's Biography |

| Note for Media: here is a press version of Matt's bio in MS Word Format or you can also use the Biography on the 2004 Athens Paralympic Games site at Matt King Bio. For a head shot photo from the 2004 Paralympic games go to www.usocpressbox.org go to photo archives (located at bottom of page), then 2004 Paralympic Games, click on cycling, then go to Matthew King |

| Matt King, blinded by

retinitis pigmentosa

(RP), an inherited incurable eye disease that gradually destroys the retina and

optic nerve, is in his seventh season

as a competitive cyclist. In this short time, he has won 12 national titles competing

in the field of American blind cyclists as well as earning fourth and second

place finishes in international Paralympic competition. But, he believes that it is his second, third, and fourth place finishes in

U.S. elite/pro (sighted) national championships that best communicate a primary

message of his sports mission: we need

not expect less from someone just because they have a disability. Low

expectations are easily learned and are one of the most common cripplers of success.

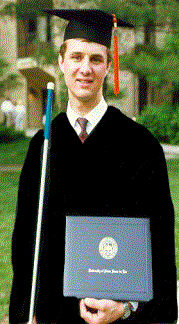

A graduate of the University of Notre Dame, Matt was born November 2, 1965 in Chehalis, Washington as the fourth of seven children. He attended public school, and his parents treated him no differently than any of his six siblings, never expecting less of him because of his slowly regressing vision. Matt is very thankful to have had such supportive parents. As a child, especially a teenager, blindness was difficult for him to handle. Speaking of those years, he says, “Even though I couldn’t walk independently at night or in dim lighting, couldn’t read normal print without bright light and lots of magnification, and even though glasses would not help, I wouldn’t ever describe myself with the label blind. I thought of ‘blindness’ as something degrading. That word made me want to shrink away. I remember getting talking books that came in cartons labeled ‘Free Matter for the Blind and Physically Handicapped’ I loved the books, but seeing that label embarrassed me. I don’t know where I learned this. I certainly did not get it from my parents. No doubt, the ridicule of teasing schoolmates who used names like ‘blindo’ and ‘klutz’ didn’t help.” Matt has always had a very competitive spirit and enjoyed physical activity. But, after one day of physical education in junior high with a teacher who had no idea how to accommodate his inability to participate in basketball and volleyball, he allowed the school counselors to excuse him from the P.E. requirements. The excuse stuck all the way through high school. “It didn’t feel right at the time. As a seventh grader, I was extremely shy, and I didn’t know what to do. I still regret not fighting that.” Unfortunately, this is a very common situation with mainstreamed blind students. |

|

| So,

Matt fueled his competitive drive with challenges in academics and

music, excelling in both. But, he did not suffer from a lack of athletic

challenges either. He grew up on a bicycle, playing on it, using it for

transportation, and even using it to earn money.

For more than six years, he raced down the rural roads of Centralia, delivering newspapers, using the route as a racecourse and always trying to better his best time. “It is amazing to reflect on what great training that was, throwing 15 to 40 pounds of paper on the front of a bike and sprinting from mailbox post to mailbox post, with a few short hills thrown in for good measure.” Not until his freshman year at Notre Dame did Matt finally have to give way to his loss of vision and stop bicycling on his own. That was an extremely difficult period of time for him, but it was also a turning point. That is when he finally came to grips with his impaired vision, recognizing it for what it was – blindness, a characteristic, a trait, not a handicap or degrading quality. (You can read about this transformation in an article Matt wrote in 1986.)

|

|

|

With Braille, a long white cane, and a switch to a tandem bicycle, Matt made the adjustment a positive one and successfully completed his college career, graduating magna cum laude with majors in electrical engineering and music. In 1995, six years after beginning his engineering career at IBM, Matt learned about the U.S. Association of Blind Athletes (USABA) through a newsletter published by the American Council of the Blind. “I had no idea how life-changing responding to that short little advertisement at the back of the Braille Forum would be,” reflects Matt. “I had always wanted to race bikes but never had the avenue. At that time I was appeasing my competitive urges by riding hard with a local bike club full of enthusiastic beginner and intermediate level racers. They are great people, we had fun and it developed a reasonably good fitness base for me, but it didn’t expose me to any truly elite or professional riders. I had very little confidence in my potential to become a seriously competitive racer at that time, but I wasn’t going to pass up an opportunity to put myself to the test. As I had often, nearly always thought in my life, if someone else can do it, why can’t I?” Just three weeks after attending a one-week training camp for new tandem racers, Matt was off to Eugene, Oregon for his first race – a five-day stage race. “We finished third in the first stage, third to last out of thirty that is. It was really hard racing. Neither my partner nor I really knew what we were doing. We had lots of equipment problems; I had a pretty horrible bike. But, somehow, we managed to claw our way up to seventeenth place in the B-category (entry level) by the end of the sixth stage of the fifth day.” In 1995, six years after beginning his engineering career at IBM, Matt learned about the U.S. Association of Blind Athletes (USABA) through a newsletter published by the American Council of the Blind. “I had no idea how life-changing responding to that short little advertisement at the back of the Braille Forum would be,” reflects Matt. “I had always wanted to race bikes but never had the avenue. At that time I was appeasing my competitive urges by riding hard with a local bike club full of enthusiastic beginner and intermediate level racers. They are great people, we had fun and it developed a reasonably good fitness base for me, but it didn’t expose me to any truly elite or professional riders. I had very little confidence in my potential to become a seriously competitive racer at that time, but I wasn’t going to pass up an opportunity to put myself to the test. As I had often, nearly always thought in my life, if someone else can do it, why can’t I?” Just three weeks after attending a one-week training camp for new tandem racers, Matt was off to Eugene, Oregon for his first race – a five-day stage race. “We finished third in the first stage, third to last out of thirty that is. It was really hard racing. Neither my partner nor I really knew what we were doing. We had lots of equipment problems; I had a pretty horrible bike. But, somehow, we managed to claw our way up to seventeenth place in the B-category (entry level) by the end of the sixth stage of the fifth day.” |

|

|

Even better than the climb to seventeenth was being spotted by Spencer Yates, one of the tandem captains from the elite category. Spencer didn’t see a seventeenth-place rider, he saw a champion in the rough. The two hit it off right away. They made arrangements to meet in Tennessee a few weeks later to race in the USABA National Road Championships. With Spencer’s guidance and real racing equipment, Matt found a sliver of new confidence. Still, the two lined up for the forty-kilometer time trial with little idea of what they really could do. Even when they crossed the line fifty-two minutes and thirty-three seconds later they had no idea what they had accomplished on that rolling Naches Trace Parkway in ninety-two degree heat and ninety percent humidity. While they were lying in the shade completely exhausted, the USABA coach ran over and told them they had posted the best time in the men’s field. Elated, the duo finished the week with another championship in the road race and began dreaming about going to the Paralympics the following summer in Atlanta. |

|

|

The dreamers began

planning immediately. They became joined at the hip. Even though they had had

some success, the challenges in front of them loomed large. First, making the

team was not only going to require good performance on the road but on the velodrome as well, and the competition

there was even more intense. It didn’t help that neither of them had much more

than a week’s experience with velodrome (or track) racing. Competing on the

velodrome meant getting a track bike;

something neither of them had. Second, getting good enough to be competitive in

Atlanta was going to mean spending a lot of time together on the bike; Spencer

lived in Tucson, Arizona; Matt lived in Poughkeepsie, New York. They found a personal coach with lots of track experience. Designs for new bikes were put to paper. Matt made arrangements for a leave of absence from IBM. And, by January, the team was living together in Tucson. After eight months of the vagabond, bike bum life, migrating their training and racing from Arizona to California to Texas to Pennsylvania, they found themselves in "the show" in Atlanta. There, they set a world record in the quarterfinals of the 4,000-meter pursuit and finished fourth in the tournament. “Atlanta was an unforgettable experience. It was not only a dream come true but also the kindler of new and bigger dreams. It was not only ineffably exciting but also incredibly eye opening. There is nothing like the Paralympics to teach someone what overcoming obstacles really means.”

|

|

|

Matt returned to New York from the Atlanta Games with more than pleasing results, new perspectives on life, and bigger bike-racing dreams. He had also been able to spend some time in person with a new friend from the United States Association of Blind Athletes (USABA) staff that he had been getting to know over the phone during the month before the games. This kindled the fire that led to his engagement to Kim Pittman five months later on December 21, 1996. In 1997, Matt moved to the U.S. Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado to prepare for the 1998 IPC World Cycling Championships and for the 2000 Paralympic Games in Sydney, Australia. His IBM management in Fishkill, NY approved of him working remotely from Colorado while following his Paralympic dream. On October fourth of the same year, Matt and Kim were married. As Spencer returned to his teaching career in Arizona, Matt began training and racing with other cyclists from the Colorado Springs area. That was the beginning of a tremendous pairing with Karen Dunne, with whom Matt shares five national titles in track racing. |

|

|

1997 was also Matt’s first year to specialize in sprint training. Matt wanted to do something more to show that he, and others like him, should be thought of as bike racers, not blind bike racers. That meant focusing on the one championship where he could compete against the best of America’s (sighted) cyclists – the men’s match sprint. In 1997, Matt and Dave Lindsay finished fourth in the U.S. Cycling Federation’s Elite Match Sprint Championships. In 1998, with partner Garth Blackburn, Matt finished with the bronze. Later that same year, Matt and Garth finished with the silver medal at the International Paralympic Committee’s World Cycling Championships. (You can read about Garth Blackburn and Matt's silver medal win featured in the Olympian Magazine)

|

|

|

Matt competed at the 2000 Paralympic Games October, 18 - 29, in Sydney, Australia, with Kirk Whiteman in the match sprints and Mark Guerin in the one-kilometer time trial. Matt and Kirk placed ninth in men’s match sprints, and Mark Guerin and Matt finished fourteenth in the men’s one kilometer time trial and sixteenth in men’s 118k road race.

In 2004, Matt and his tandem partner, Eric DeGolier, will represent the USA at the 2004 Paralympic Games, September 17 - 28, in Athens, Greece. They will compete in the one-kilometer time trial, the match sprints, and the road race. |

|

|

Matt and his wife, Kim, have a daughter, Lavyn, who will turn 3-years old just after the Athens Games. Their second child will be born in December. (photo to the right - Matt and Lavyn, Matt and Kim's daughter at almost 3 months old, carry the Olympic Torch).

|

|